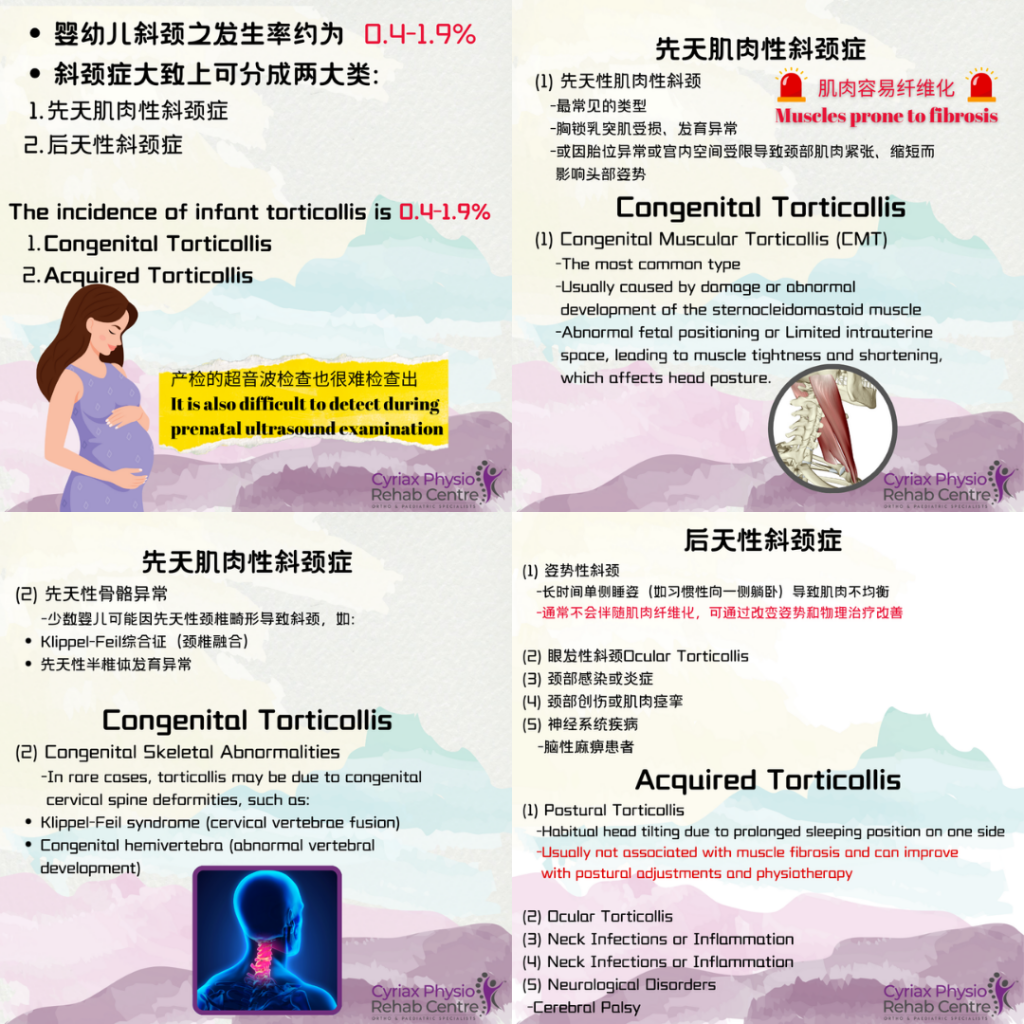

The incidence of infant torticollis is approximately 0.4-1.9%. It can be broadly classified into two main types:

- Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT)

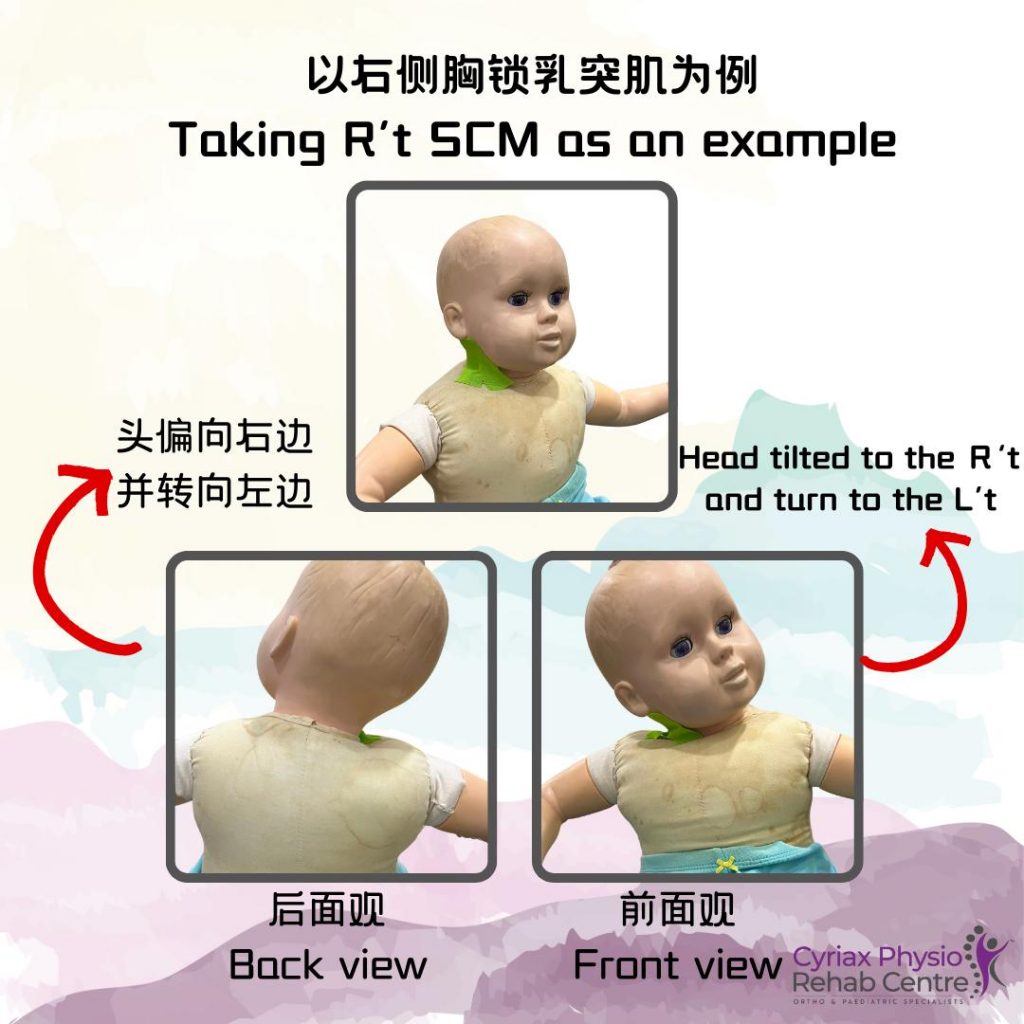

- The most common type, usually caused by tightening or fibrosis of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, leading to the infant’s head tilting to one side while the chin points in the opposite direction.

- It may be related to abnormal fetal positioning, birth trauma (such as the use of forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery), or intrauterine constraints.

- Early detection and intervention (such as physiotherapy, manual therapy, and posture correction) are typically effective in improving the condition.

- Acquired Torticollis

- Postural Torticollis: Often caused by poor posture, neck muscle tightness, or asymmetrical sleeping positions. It can usually be improved through postural adjustments and physiotherapy.

- Ocular Torticollis: Caused by eye disorders (such as strabismus or refractive errors), where the infant tilts their head to adjust their vision. This type requires an ophthalmologic assessment and appropriate treatment.

Treatment and Management

- Early diagnosis and physiotherapy (such as passive stretching and active exercises) can effectively improve congenital muscular torticollis.

- Postural torticollis can be managed by adjusting sleeping positions and encouraging symmetrical movements.

- Ocular torticollis should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist to determine whether glasses or other corrective treatments are needed.

Causes of Torticollis in Infants

Torticollis (wry neck) in infants can be categorized into congenital and acquired types, each with different causes.

1. Congenital Torticollis

(1) Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT)

This is the most common type, usually caused by damage or abnormal development of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, leading to muscle tightness and shortening, which affects head posture.

- Prenatal factors:

- Abnormal fetal positioning (e.g., breech or transverse position) that exerts pressure on the neck

- Limited intrauterine space (e.g., multiple pregnancies, oligohydramnios) restricting fetal neck movement

- Perinatal factors:

- Birth trauma (e.g., forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery) can cause SCM injury or bleeding, leading to muscle fibrosis

- Postnatal factors:

- Imbalance in muscle strength leading to head tilt

(2) Congenital Skeletal Abnormalities

In rare cases, torticollis may be due to congenital cervical spine deformities, such as:

- Klippel-Feil syndrome (cervical vertebrae fusion)

- Congenital hemivertebra (abnormal vertebral development)

2. Acquired Torticollis

Acquired torticollis can develop weeks, months, or even years after birth due to various reasons, including:

(1) Postural Torticollis

- Habitual head tilting due to prolonged sleeping position on one side

- Neck movement restrictions leading to asymmetrical posture

- Usually not associated with muscle fibrosis and can improve with postural adjustments and physiotherapy

(2) Ocular Torticollis

Caused by eye disorders that lead to abnormal vision alignment, prompting the child to tilt their head to compensate. Common conditions include:

- Strabismus (misalignment of the eyes)

- Refractive errors (e.g., farsightedness, astigmatism)

- Superior oblique muscle palsy (weak eye muscles causing compensatory head tilt)

An ophthalmologic evaluation is needed for proper correction (e.g., glasses or surgery).

(3) Neck Infections or Inflammation

- Lymphadenitis (swollen lymph nodes due to viral or bacterial infections) may cause pain and a tilted head posture

- Throat infections or ear infections can lead to reflexive neck muscle spasms

(4) Neck Trauma or Muscle Spasms

- Neck strain or injury (e.g., falling, impact)

- Nutritional deficiencies (e.g., calcium or magnesium deficiency) can lead to muscle tightness or spasms

- Side effects of certain medications (e.g., acute dystonia caused by some antipsychotic drugs)

(5) Neurological Disorders

- Cerebral palsy can cause torticollis due to abnormal muscle tone

- Spasmodic torticollis (a rare condition more common in adults, involving neurological dysfunction)

How to Determine the Type of Torticollis?

- Palpate the sternocleidomastoid muscle for any lump (may indicate CMT)

- Observe head posture to check for visual problems, pain, or restricted movement

- Examine neck symmetry to rule out skeletal abnormalities

If an infant shows persistent torticollis for more than 2-3 weeks, early medical evaluation is recommended to prevent potential developmental issues in head and neck symmetry.

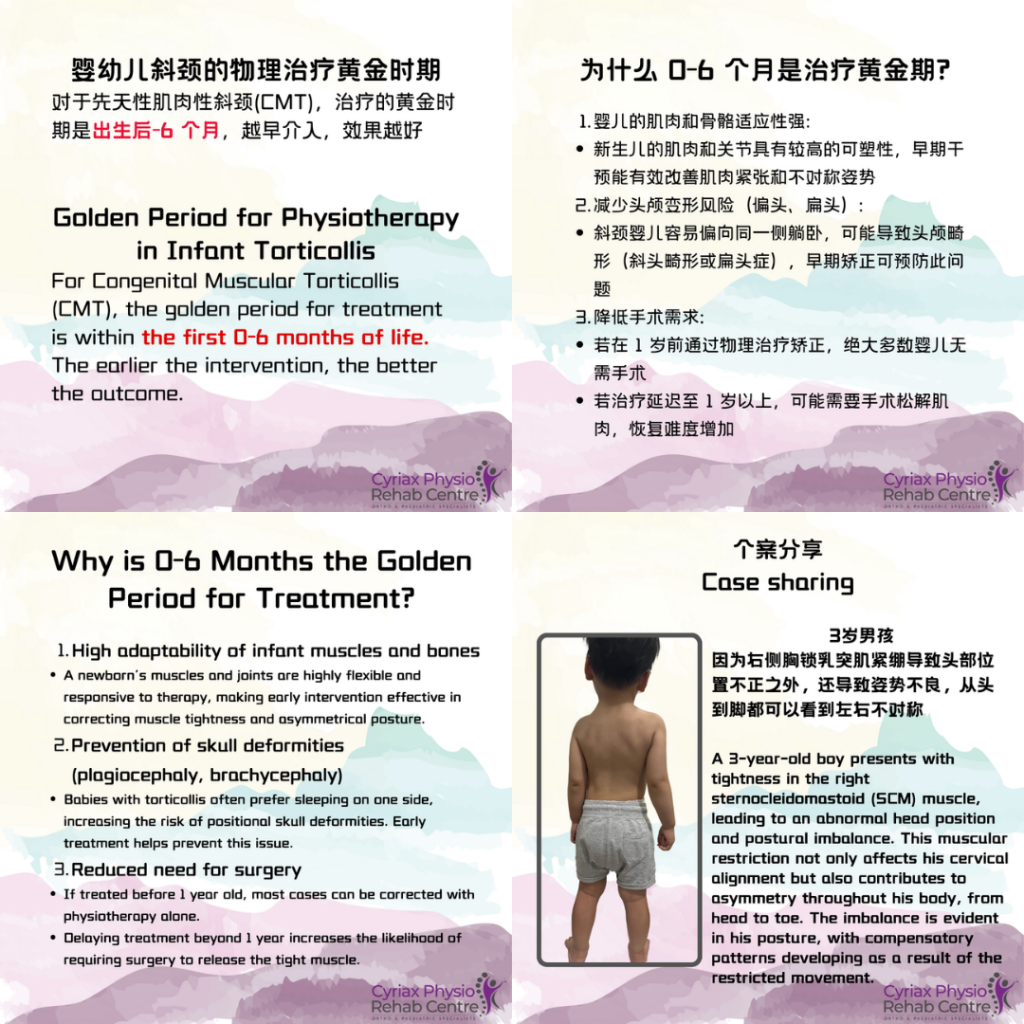

Golden Period for Physiotherapy in Infant Torticollis

For Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT), the golden period for treatment is within the first 0-6 months of life. The earlier the intervention, the better the outcome.

Why is 0-6 Months the Golden Period for Treatment?

- High adaptability of infant muscles and bones

- A newborn’s muscles and joints are highly flexible and responsive to therapy, making early intervention effective in correcting muscle tightness and asymmetrical posture.

- Prevention of skull deformities (plagiocephaly, brachycephaly)

- Babies with torticollis often prefer sleeping on one side, increasing the risk of positional skull deformities. Early treatment helps prevent this issue.

- Reduced need for surgery

- If treated before 1 year old, most cases can be corrected with physiotherapy alone.

- Delaying treatment beyond 1 year increases the likelihood of requiring surgery to release the tight muscle.

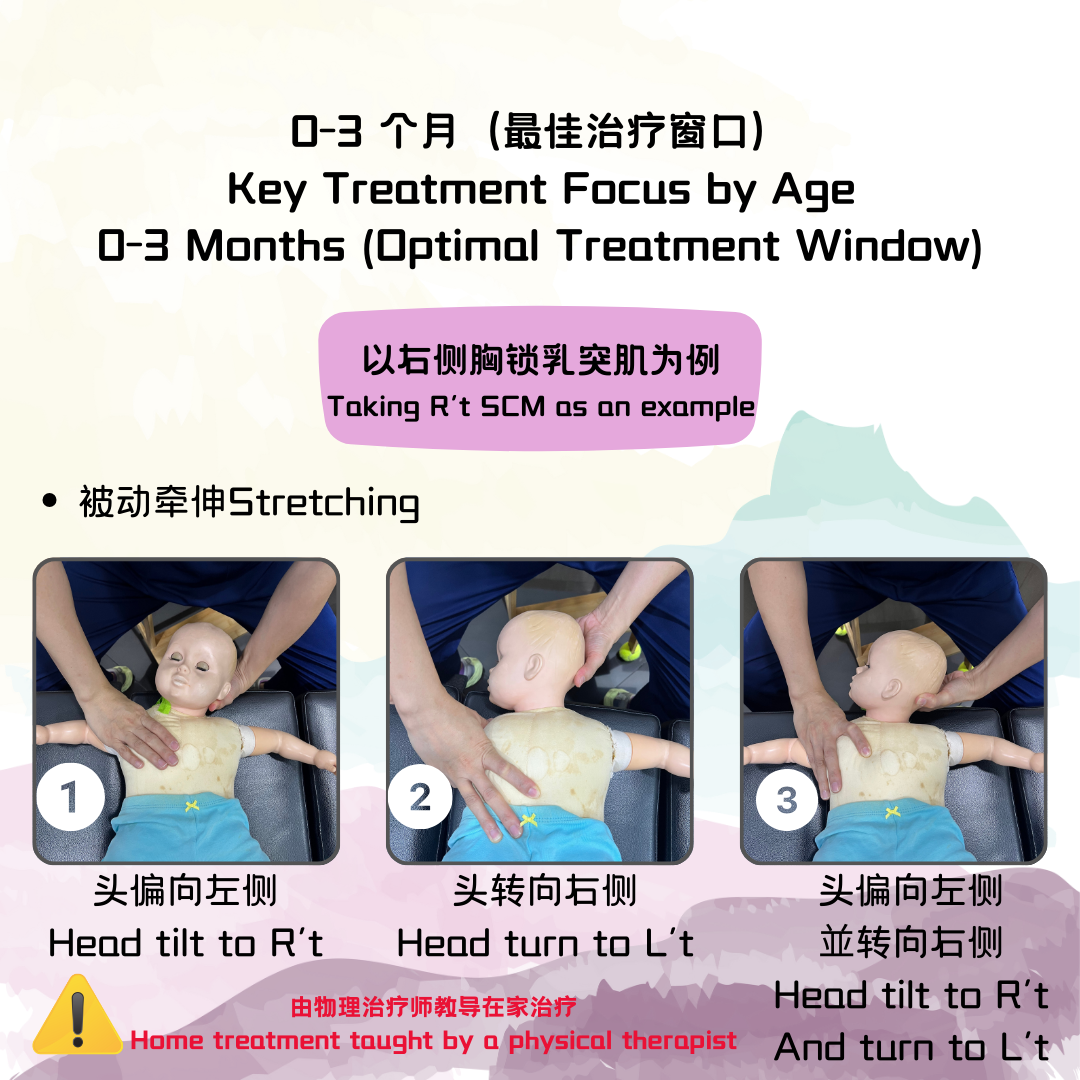

Key Treatment Focus by Age

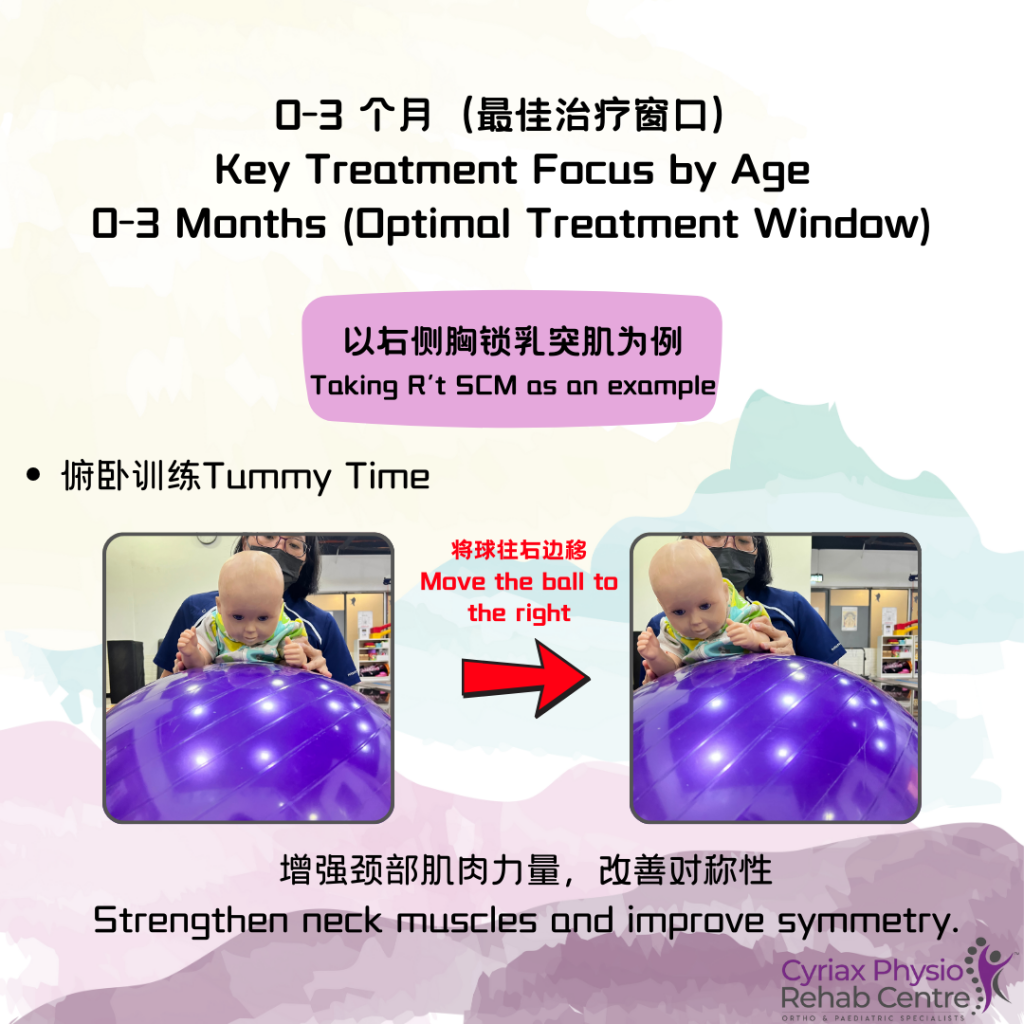

✅ 0-3 Months (Optimal Treatment Window)

- Passive stretching: Parents, under the guidance of a doctor or physiotherapist, should perform gentle daily stretching of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle.

- Postural adjustments: Encourage the baby to turn their head towards the restricted side by changing feeding positions, crib placement, and using visual stimuli.

- Tummy time exercises: Strengthen neck muscles and improve symmetry.

✅ 3-6 Months (Still Within the Golden Period)

- Increase active movement training, encouraging the baby to turn their head and reach for toys.

- Use visual and auditory stimulation by placing toys or sounds on the less preferred side.

✅ 6-12 Months (Treatment Still Possible but Slower)

- If torticollis persists beyond 6 months, intensified physiotherapy may be needed, including manual therapy.

- Assess for skull deformities (e.g., flat head syndrome), which may require helmet therapy.

✅ 12 Months and Above

- If the condition does not improve, imaging tests (e.g., X-ray) may be required to check for skeletal abnormalities.

- Severe cases may require surgical intervention (e.g., SCM muscle release surgery).

Success Rate of Physiotherapy

- If therapy begins within the first 3 months, the success rate is 90-95%, and most babies recover fully.

- Delaying treatment beyond 1 year reduces effectiveness and increases the likelihood of requiring surgery.

🔹 0-3 months is the best time for intervention, and 0-6 months is still within the golden period. Early assessment and treatment are strongly recommended.

🔹 Early physiotherapy can prevent long-term issues, such as head deformities, muscle contractures, and postural imbalances.